Why celebrity book clubs aren't the best (even with Oprah)

Oprah’s Book Club stamp does more for book sales than the Nobel Prize, at least according to the numbers for the late Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Sula, The Bluest Eye, and Paradise. Oprah has single-handedly lifted up some authors; printings of little-known “Say You’re One of Them” by Uwem Akpan saw a tenfold increase after receiving the recognition. Leo Tolstoy would’ve felt like he’d been struck by the Trans-Siberian Express after Anna Karenina was honored as a OBC pick and made it to the top of the bestsellers’ lists 140 years after its publication.

Endorsements like Oprah’s and Reese Witherspoon’s Book Clubs clearly matter. They influence the public’s exposure to specific texts, they direct publicity dollars to specific authors, and they focus the audiences’ attention on specific issues. But what does all that concentrated power mean for our shared reading experience? And how can we be sure that the best, most diverse selection of books are making it to the top of this rarified funnel?

When celebrity book clubs pick the wrong book

American Dirt, chosen by Oprah’s Book Club, has been making opinion-page headlines. In it, author Jeanine Cummins writes about a mother and son fleeing for the United States after their family is killed by a drug cartel. Cummins wanted to humanize the conversation around the U.S.-Mexico border and immigration, but has been criticized for not only telling the story of other peoples’ experiences, but telling it poorly.

Cummins’s white identity is central to the uproar, and it has once more sparked the very worthy discussion of who should be the storytellers, especially about people who so often bear the brunt of heightened partisan rhetoric and overwrought stereotypes (“calves the size of watermelons,” anyone?).

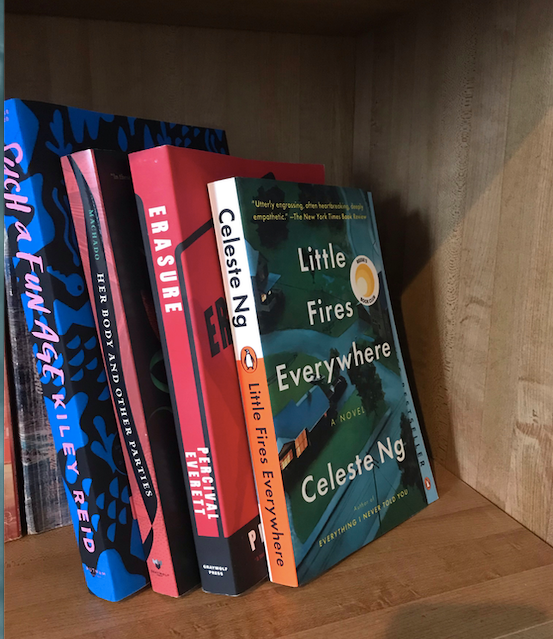

The ever-creative writer Percival Everett gets at this in his 2001 novel Erasure. In that book, he deftly criticizes not only the authors who tell lazy stories drawn from stereotypes but also the industry that promotes the stories and public who greedily consumes them because the stories comfortably confirm their own biases. Within Erasure itself Everett embeds a satiric novella that is an obvious parody of Richard Wright’s Native Son, another book that was received with fanfare but that critics including James Baldwin criticized for offering exaggerated characters who do more harm than good in trying to provide a glimpse of the black American experience.

And this becomes more hazily problematic if there are books that people clearly connect with — like Reese Witherspoon’s overwhelmingly popular pick Where the Crawdads Sing, that are full of compelling natural scenes and melodrama but that also rely on uncomfortable tropes like the benevolent older black woman providing advice and counsel and comfort to the young, beautiful white woman protagonist.

What celebrity book selections mean to publishing

Even setting the issue of authorship aside, this calls for a closer look at what it means when a book of questionable caliber — whether it is perpetuating harmful biases or just kind of a drip to read — gets the full weight of the publishing machine behind it. What does that momentum do?

Obviously, based on Oprah’s numbers, it sells books. Books let people get a glimpse into other peoples’ lives, potentially building empathy for the experience of the Other. But when that glimpse is a flawed one, an inaccurate one, an offensive one, that can do more harm than good. Selling millions of books (and getting people to read them) is a great goal in itself, but it also ups the stakes for the impact those books will have on public narratives.

More books sold may translate to more books read, yes. But troublingly, these endorsements essentially “crowd out” other literature, other new authors, other voices. The American Economic Association’s Craig Garthwaite studied the demand spillover effects of the strong marketing that comes from celebrity endorsement, and found that the endorsements don’t lead to more readers, they just direct existing readers to specific books and increase those specific books’ market share. The endorsed titles and authors essentially cannibalize, or crowd out, other authors. And this continues a particular problem if those are the voices that tend to get crowded out in general.

Who we place at the center of plots and conversations does matter. Just look at August Thomas, a woman who wrote Liar’s Candle and created a plot without the typical spy-thriller genre’s gratuitous violence toward women. Or Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, a collection of magical and compelling stories that do explore that gratuitous violence toward women in an intimate and emotional way.

Picking books beyond Reese, Oprah, Jenna, Gwyneth, Emma or any other book club

More diversity — of thought, discussion, opinions, and characters — brings out the best of what we love about reading. And avid readers are far from passive consumers.

So while it's great to celebrate more awareness and attention for books, lets not blindly assume that the small number of books who receive the vast majority of publishing budgets and celebrity attention are the only ones of value.

At Italic Type, we are hoping to heighten the best book club books by understanding and promoting those books that generate the most discussion and recommendations from real readers who have no agenda other than the fact the love to read, learn, and discuss.